Checklist 1: Words and Phrases

Checklist 2: Past Tense Phrases

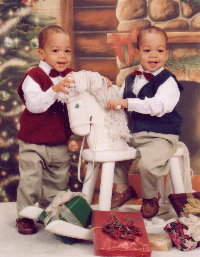

The MIT Twins Study is a long-term study of language development in twins which began in June, 1995 as part of Jennifer Ganger's Ph.D dissertation, supervised by Steven Pinker and Kenneth Wexler. As of August 2002, there have been over 800 pairs of twins that have participated in this study. It is supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to Professor Steven Pinker, by a McDonnell-Pew Center for Cognitive Neuroscience grant to MIT, by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Training Grant to Professors Kenneth Wexler and David Pesetsky, and by the Mind Articulation project at MIT.

The aim of this project...

is to collect measures of language development for a large number of identical and fraternal twins over a long period of time, starting at around 10 months of age. To that end, we have asked parents of twins, scattered throughout the United States, to keep careful track of their twins' linguistic developmental milestones, from first words to past tense marking. Although this study depends on parental report and will necessarily miss a lot of details we might otherwise be able to obtain, it nonetheless contains more detail than has ever been gathered in a study of its kind. There are currently about 150 families with twins participating in our study and the number is growing. This study is called the "Checklist Study." Click here to find out what do if you're interested in having your twins participate.

Why are we interested in language development in twins?

Decades of research have implicated a genetic component to language. Some evidence for this conclusion comes from the study of linguistic universals: all human languages seem to have certain structural motifs in common despite vast surface variation and large distances between them. Other evidence comes from developmental studies: there are developmental disorders in which language may be spared while other functions are compromised, and there are disorders specific to language, where it is the only affected system. Furthermore, language disorders such as Selective Language Impairment (SLI) and dyslexia have been found to have a pattern of inheritance in families and in some cases has been localized to a particular chromosome. Still more arguments can be made from learnability considerations and from the development of language in certain populations of children despite sparse linguistic input (i.e., creolization).

Clearly language cannot be completely genetically predetermined like eye color or the function of the liver. The very fact that languages differ greatly in surface form and use attests to this. However, to date, little research has been conducted to specify which components of language are genetically linked. The study of language development in the absence of rich linguistic input contributes to this goal, but by using the study of an abnormal situation rather than a normal one. Another way to answer this question is by studying twins.

Monozygotic twins share 100% of their genes, so we expect aspects of their behavior which have a genetic link to be highly correlated. Dizygotic twins, on the other hand, share (on average) 50% of their genes (assuming no assortive mating), just like non-twin siblings. We therefore expect these twins to differ in at least some genetically determined traits. By finding correlations for the same traits for monozygotic and dizygotic twins and calculating the difference between these correlations, we may estimate the heritability component of the traits we measured (see, e.g., Plomin, 1978).

Although some studies of normal language development in twins have been reported, these have tended to focus only on the development of vocabulary and certain fixed expressions (e.g., Reznick, 1994), or they are limited in scope, testing a large number of twins only once or twice on a certain measure, rather than studying developmental trends in detail (e.g., Mather & Black, 1984; Munsinger & Douglass, 1976). Some of these studies have implicated a heritable component in their measures, some have not.

Our hope is that by studying important aspects of language acquisition in more detail than has ever been done before, we may gain further insight into the genetic basis of language.